Chronic pelvic pain (CPP), defined by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists as pain unrelated to pregnancy, perceived to originate from pelvic organs/structures, and typically lasting for more than 6 months,1 is a challenging clinical condition for physicians and patients alike. In addition to the significant and detrimental physical and psychological effects of chronic pain, CPP can often affect a woman’s daily activities and result in significant emotional, psychosocial, and financial distress. CPP affects up to 24% of women globally. Some studies have shown it can take an average of 4 to 11 years of seeing multiple specialists before a woman gets proper diagnosis and treatment because of various factors including limited health care access, lack of clinician knowledge, and reduced availability of effective treatment options. This is further compounded by the multiorgan involvement of the pelvic area and lack of coordinated multidisciplinary care. Up to 40% of patients with CPP are affected by more than 1 overlapping pain condition, typically accompanied by poor mental and physical health.2 Recent data suggest patients with CPP are more likely to be prescribed opioids with higher doses used.3 CPP is often categorized by organ systems including the genital organs, the urinary tract, colorectal structures, the vascular system, and the surrounding musculoskeletal architecture.4

Takeaways

- Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) can be a challenging condition to diagnose and manage.

- Up to 85% of women with CPP also have a component of hypertonic pelvic floor dysfunction with tight pelvic muscles, which may be a significant contributor to their pain symptoms.

- The diagnosis of myofascial pelvic pain is predominantly clinical based on presenting symptoms and exam findings of pelvic floor trigger points.

- Traditional therapies are associated with variable results, poor adherence, and lack of follow-up.

- Photobiomodulation is emerging as a safe and effective therapy for many musculoskeletal disorders, including myofascial pelvic pain.

The most common causes of CPP considered by treating clinicians include endometriosis, adenomyosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, bladder pain syndrome, recurrent cystitis, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease, and pelvic congestion syndrome. Conditions of the musculoskeletal structure, specifically of the pelvic floor muscles, are infrequently considered, resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment. In fact, recent studies suggest that up to 85% of women with CPP have a component of hypertonic pelvic floor dysfunction also known as myofascial pain, levator spasm, or pelvic floor tension myalgia5 This occurs when the pelvic floor is in a chronic tight state presenting as pain, especially with sexual intercourse, defecation, and urination.

Patients can present with chronic aching pain with flares and radiation to the lower abdomen, lower back, hips, and upper extremities. Some women can present with lower urinary tract symptoms or vaginal pain but with negative cultures. Tightness of the pelvic floor muscles can also affect the pelvic nerves and mimic conditions such as pudendal neuralgia. Central sensitization syndrome, an adaptive response of the central nervous system resulting in hyperalgesia, allodynia, and global sensory hyperresponsiveness, commonly develops in patients with CPP, further complicating treatment. Pain symptoms can be further exacerbated by triggers including sexual activity, physical exercise, bladder or vaginal infections, prolonged sitting, constipation, or stress. Diagnosis is often delayed, as many clinicians are unfamiliar with the condition and do not consider it in the differential diagnosis. Furthermore, there are no definitive imaging or lab studies to exclude or confirm the diagnosis. Fortunately, the diagnosis is easily confirmed on manual pelvic exam with palpation of the individual pelvic floor muscles to assess tone, evaluate for allodynia and tenderness (pelvic floor trigger points), and reproduce the presenting pain symptoms.

Many patients with CPP may have myofascial pain in addition to core pathologic processes, and it is important to consider both in the differential diagnosis and the etiology for treatment. The primary process may have served as the trigger for myofascial pain, which may then represent the main component of pelvic pain. In addition, treatment of the primary process without consideration and treatment of the hypertonic component may result in a patient with persistent pain symptoms. In a recent study of endometriosis patients with persistent pelvic pain and pelvic floor trigger points on exam, botulinum toxin (Botox) injections to the pelvic floor resulted in significantly less postinjection spasm and pain, suggesting that endometriosis patients with signs of pelvic myalgia may have a predominant component of hypertonic pelvic floor dysfunction contributing to their persistent pain.6 Anecdotally, pelvic floor physical therapy (PT) with myofascial release has been advocated by many as first-line therapy for CPP syndromes including vulvodynia, dyspareunia, bladder pain syndrome, and mesh-related pelvic pain, further suggesting a pelvic floor muscular etiology or component in many of these pelvic pain conditions.

Current treatments

Until recently, treatment options for myofascial pelvic pain have been suboptimal. Traditional treatments include oral and vaginal medications including muscle relaxants, pelvic floor PT referral, pelvic floor trigger point injections, vaginal botulinum toxin, and even more invasive procedures including sacral neuromodulation. Results are suboptimal owing to a variety of factors including lack of access, operator-dependent results, poor patient adherence, significant adverse reactions, lack of long-term positive outcomes, and financial constraints due to noncovered services (Table). Most therapies are considered off label for the indication of pelvic pain or levator spasms, and results regarding safety and efficacy are limited. In addition, many patients suffer from concurrent central sensitization syndrome from prolonged pain, which may not respond to therapies targeted to the pelvic floor. Early diagnosis and treatment are key.

Pelvic floor PT has become the mainstay of treatment despite variable results and poor adherence. One of the earlier randomized controlled trials comparing pelvic floor PT to conventional massage reported 59% of women undergoing PT reported a meaningful reduction in pelvic pain compared with 26% of women in the control group. The PT group experienced mean pain reduction of approximately 37%.7 Unfortunately, many patients find access to a physical therapist experienced in hypertonic floor dysfunction difficult, and the treatments can often be painful, with high discontinuation rates. Woodburn studied 660 patients referred to pelvic floor PT and reported only 20% of patients were adherent to the recommended length of treatment and only 40% returned to their gynecologist.8 There is need for a treatment option that is widely available, on label, safe, effective, independent of operator-based variation, and associated with high adherence rates.

Photobiomodulation (PBM) is the science of applying light waves to human tissue to cause a biologic effect. This technology has been used for over 20 years in the treatment of muscle pain and spasm with proven efficacy for the treatment of low back pain, fibromyalgia, and knee and shoulder pain.9,10 PBM therapy uses nonablative near-infrared light to trigger biochemical changes within cells, predominantly affecting mitochondrial respiration and cytochrome c oxidase. This results in increased production of ATP and release of nitric oxide, which is a powerful relaxer of both smooth and skeletal muscle and can reduce muscle pain, decrease inflammation, and improve circulation and oxygenation to tissues.11 Thousands of published studies have validated the safety and efficacy of PBM, and over 1.5 million PBM procedures are performed monthly, according to Lite-Cure internal data.

SoLá Pelvic Therapy Laser

The SoLá Pelvic Therapy Laser, introduced by Uroshape, LLC, is the only PBM device currently available for vaginal use and cleared for treatment of CPP and pelvic floor muscle spasm. The device consists of a self-contained mobile unit incorporating a nonablative class IV near-infrared laser transmitting at both 810-nm and 980-nm wavelengths (Figure 1). It includes an interactive cloud-connected touch screen that enables patient demographic and symptom data collection as well as regulates delivery of the therapeutic fluence based on length of the vagina. The standard treatment protocol involves 9 treatments provided over a period of 3 to 6 weeks—typically 3 times per week. Each treatment is delivered through a vaginal probe with a disposable tip and ranges from 1 to 4 minutes with a metronome-style graphic interface to ensure consistent treatment. The treatments are not painful, and many patients describe a gentle warming sensation during delivery of the light energy. Prior to each treatment, patients complete the standardized patient questionnaire on the touch screen, which is used to monitor individual patient progress and to collect and analyze deidentified large-scale data in real time. Patients also have access to their individual data to track treatments and response as well as obtain pelvic pain patient education through an associated mobile app.

Patients who have CPP and pelvic floor trigger points on vaginal exam are candidates for therapy. There are relatively few contraindications to the treatment including pregnancy, active vaginal infection or UTI, unexplained or active vaginal bleeding, cancer of the urogenital tract, patients with decreased sensation in the vagina or rectum, or patients taking medications that are heat or light sensitive. The safety of PBM has been well-established in the extensive published literature. Adverse effects specific to SoLá therapy are mild and self-limited and include transient increase in vaginal discharge associated with increased blood flow and temporary increase in irritative voiding symptoms/overactive bladder or pelvic pain especially in patients with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome.

Results

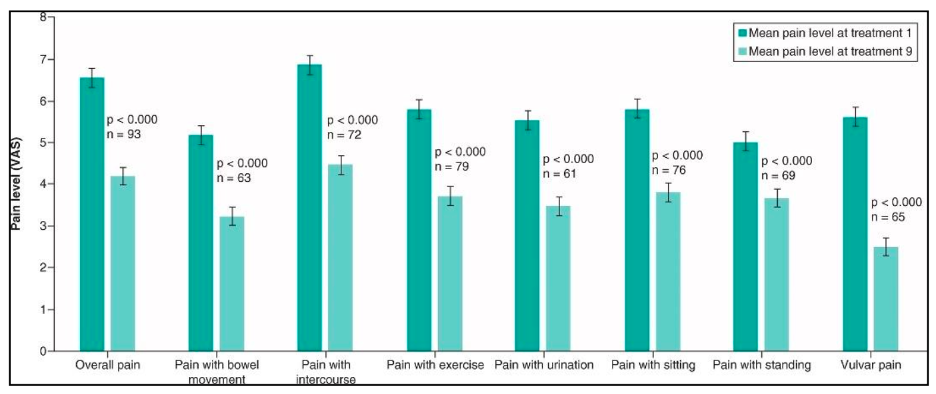

Most patients report initial improvement in their symptoms after the third treatment and continued response with each subsequent treatment. Clinical efficacy and patient adherence rates are high. In the first published analysis of 144 patients undergoing SoLá therapy for CPP with various clinical conditions, 128 (89%) opted to undergo complete therapy. Of the 128 patients evaluated, 93.0% (n = 119) completed 4 treatments, 89.8% completed 5 treatments, 72.7% (n = 93) completed all 9 recommended treatments, and 52.3% (n = 67) opted for additional therapy beyond 9 treatments. At baseline, all patients had CPP; however, 66.4% (n = 85) also reported pain with bowel movements; 78.1% (n = 100), pain with intercourse; 82.8% (n = 106), pain with exercise; 65.6% (n = 84), pain with urination; 82.8% (n = 106), pain with sitting; 74.2% (n = 95), pain with standing; and 70.3% (n = 90), vulvar pain. The women in this analysis had a wide-ranging prevalence of self-reported pain comorbidities (44% interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome [IC/BPS]; 14%, endometriosis; 50%, dyspareunia; 70%, vulvar pain) and symptom-specific pain (66%, pain with bowel movements; 78%, pain with intercourse; 83%, pain with exercise; 66%, pain with urination; 83%, pain with sitting; and 74%, pain with standing). Eighty percent had pain lasting longer than 1 year.

The primary outcome of this study was the minimal clinically significant difference (MCID), defined as pain improvement of greater than 2 points on the Numerical Rating Scale measuring overall pelvic pain. The study found that compared with baseline, clinically significant improvement in overall pain was reported by nearly 65% of the women who completed at least 8 treatments, and Cohen’s coefficient of effect size was medium high for nearly all types of pain studied, including pain with sitting, standing, intercourse, defecation, and activity (Figure 2). Ninety percent of all patients completed at least 5 treatments, which is notable because the largest improvement in pain was noted in the first 4 treatments, although additional improvements were described between 5 and 9 treatments (Figure 3). Moreover, pain improvement was noted regardless of the diagnosis associated with the pain, meaning SoLá Pelvic Therapy was effective in patients with a variety of pelvic pain conditions such as endometriosis, IC/BPS, IBS, and vulvodynia. During the study period, there were no serious adverse events or unanticipated adverse events reported.12 A second prospective observational pilot study conducted by Zipper et al involving a different cohort of patients indicated that the therapeutic effect may last as long as 6 months.12 This finding was similar to a follow-up analysis by Kohli et al, using data obtained from the SoLá Pelvic Therapy database. In this analysis, they followed 101 consecutive patients who were treated with SoLá Pelvic Therapy and found that 87% remained improved at 6 months.13

The latest analysis of the SoLá database shows that overall, from 2019 to 2022, 695 patients with significant CPP evaluated in 22 clinics across 16 states were offered a trial of SoLá Pelvic Therapy. Of the ones who were introduced to therapy, 72.6% (n=505) opted to continue therapy beyond the trial and 86% (n=437) completed all 8 recommended treatments. Of those who completed treatment, 81.4% (n=355) reported significant decrease (MCID≥2) in overall pelvic pain, pain with exercise, and pain with intercourse (dyspareunia). Additionally, 60.9% of the cohort reported minimal or no overall pelvic pain at the end of 8 treatments compared with 27.0% at baseline, according to the 2023 Uroshape Sola Therapy Database. Anecdotally, many patients reported concurrent improvement of overactive bladder or irritative voiding symptoms, suggesting a neuromuscular pelvic floor etiology to these symptoms.

Posttreatment

There are currently no standardized posttreatment protocols, and patients should be managed on an individualized basis. Following treatment, many patients maintain good pain control with behavioral modification and avoidance of pelvic pain triggers, while others benefit from pelvic floor PT with myofascial release or use of compounded muscle relaxants, vaginal suppositories, or a combination of these treatment options. Others benefit from intermittent maintenance SoLá therapy, which typically consists of 3 treatments over 1 week at a preselected interval for prevention or treatment with flares. Close follow-up for the first year with aggressive intervention for flares is recommended. Patients with persistent pain following therapy should be evaluated with repeat exam. Often, the myofascial pain component has resolved, and patients may have continued pain due to a primary process or central sensitization syndrome. Coordination with a pain clinic with a multidisciplinary approach including anesthesia pain specialists, pain psychologists, and behavioral modification is beneficial.

Conclusion

CPP can be a challenging condition to diagnose and manage. Up to 85% of women with CPP also have a component of hypertonic pelvic floor dysfunction with tight pelvic muscles, which may be a significant contributor to their pain symptoms. The diagnosis of myofascial pelvic pain is predominantly clinical based on presenting symptoms and exam findings of pelvic floor trigger points. Traditional therapies are associated with variable results, poor adherence, and lack of follow-up. PBM is emerging as a safe and effective therapy for many musculoskeletal disorders including myofascial pelvic pain. SoLá therapy has been shown to provide safe, effective, and durable therapy for patients suffering from myofascial pain and a variety of associated pelvic floor symptoms. Initial results are encouraging, and large-scale studies are in progress, with a randomized prospective sham trial on the horizon. Patients are best treated with a multidisciplinary approach, and SoLá therapy may be an effective clinical tool to consider in the treatment of patients with persistent and debilitating pelvic pain.

References:

- CPP: ACOG practice bulletin, number 218. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(3):e98-e109. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003716

- Lamvu G, Carrillo J, Ouyang C, Rapkin A. CPP in women: a review. JAMA. 2021;325(23):2381-2391. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.2631

- Cichowski SB, Rogers RG, Komesu Y, et al. A 10-yr analysis of CPP and chronic opioid therapy in the women veteran population. Mil Med. 2018;183(11-12):e635-e640. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy114

- Juganavar A, Joshi KS. CPP: a comprehensive review. Cureus. 2022;14(10):e30691. doi:10.7759/cureus.30691

- Meister MR, Sutcliffe S, Badu A, Ghetti C, Lowder JL. Pelvic floor myofascial pain severity and pelvic floor disorder symptom bother: is there a correlation? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(3):235.e1-235.e15. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.07.020

- Tandon HK, Stratton P, Sinaii N, Shah J, Karp BI. Botulinum toxin for CPP in women with endometriosis: a cohort study of a pain-focused treatment. Published online July 8, 2019. Reg Anesth Pain Med. doi:10.1136/rapm-2019-100529

- FitzGerald MP, Payne CK, Lukacz ES, et al. Randomized multicenter clinical trial of myofascial physical therapy in women with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome and pelvic floor tenderness. J Urol. 2012;187(6):2113-2118 doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.01.123

- Woodburn KL, Tran MC, Casas-Puig V, Ninivaggio CS, Ferrando CA. Compliance with pelvic floor physical therapy in patients diagnosed with high-tone pelvic floor disorders. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(2):94-97. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000732

- Clijsen R, Brunner A, Barbero M, Clarys P, Taeymans J. Effects of low-level laser therapy on pain in patients with musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;53(4):603-610. doi:10.23736/S1973-9087.17.04432-X

- Yeh SW, Hong CH, Shih MC, Tam KW, Huang YH, Kuan YC. Low-level laser therapy for fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Physician. 2019;22(3):241-254.

- de Freitas LF, Hamblin MR. Proposed mechanisms of photobiomodulation or low-level light therapy. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron. 2016;22(3):7000417. doi:10.1109/JSTQE.2016.2561201

- Kohli N, Jarnagin B, Stoehr AR, Lamvu G. An observational cohort study of pelvic floor photobiomodulation for treatment of CPP. J Comp Eff Res. 2021;10(17):1291-1299. doi:10.2217/cer-2021-0187

- Zipper R, Pryor B, Lamvu G. Transvaginal photobiomodulation for the treatment of CPP: a pilot study. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle). 2021;2(1):518-527. doi:10.1089/whr.2021.0097

- Kohli N, Jarnagin B, Stoehr A. Treatment of myofascial pain with a novel transvaginal photobiomodulation laser. Neurourol Urodyn. 2021;40:S6-S242.